In the present day, vicious spines and large, undispersed seeds are the "Ghosts of Megafauna Past" of the Amazon rainforest – adaptations of plants that co-evolved over evolutionary time with native megafauna but have not yet caught on to their absence in the past ~10,000 years.

I distinctly remember the first time I accidentally stabbed my hand on the spine of an Astrocaryum palm, and thinking to myself, "Why on Earth does this plant possess such horrendously vicious spines?!" Surely it can’t be for protection – even the largest Amazonian rainforest animal, the tapir, is nowhere near large or strong enough to knock over a tree, as African elephants are known to do. The leaf bases of young Astrocaryum palms resemble a medieval torture instrument, covered in shiny black dagger-like protrusions often more than a foot in length, with wide bases terminating in an exceedingly sharp tip – so sharp that you may not even realize that you’ve been stabbed by one until you notice the blood dripping from the puncture wound…or, to add insult to injury, when you notice the spine dangling hideously from your arm. I would like to name this trees like the Megafauna of the past.

The Astrocaryum palm is notorious for its vicious spines by Varun Swamy

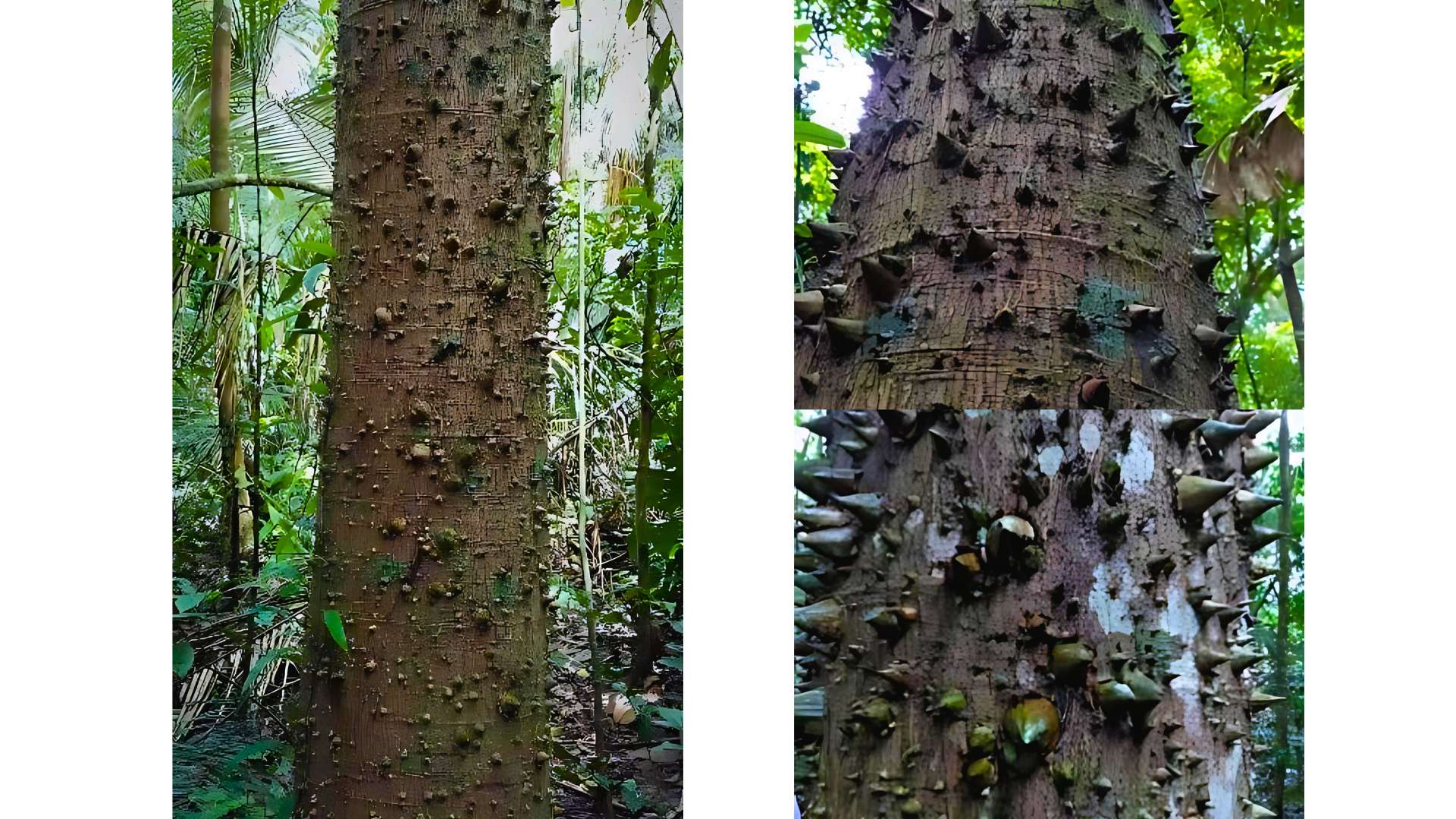

Over years of doing research in the Amazon rainforests of Peru, I have had unpleasant firsthand encounters with other species of trees armed with what I would consider "unreasonably" vicious spines covering their trunks – the large conical spines of Jacarartia digitita, the distinctly compressed planar spines of Zanthoxylum, the numerous small but no less vicious spines on the trunks of young Ceiba trees, to name a few. In every instance, a yelp of pain as spine and skin made contact was followed by a string of expletives and (even after I eventually learned the answer) a plaintive "Why…?!"

Jacarartia digitita, a fast-growing Amazon rainforest tree armed with large conical spines by Varun Swamy

Over the same period, my research has focused on understanding the impact of unsustainable hunting of native seed-dispersing mammals and birds like spider monkeys, tapirs, guans and trumpeters on the composition and structure of rainforest vegetation. In doing so, I have invested a lot of time and effort in determining the primary dispersal agent of tree species with fleshy fruits – either by direct observation, or by deduction based on the size, color and distinct architecture of fruits and seeds. And therein I encountered another ecological mystery – a small but distinct group of trees with enormous fruits and seeds, way too large to be dispersed in the classic "enzoochorous" manner (swallow fruit whole, poop seed intact) by any native rainforest animal.

Two particularly striking examples of these undispersed and seemingly "undisperseable" seeds are Calatola venezuelana and Caryocar amigdaliforme. Year after year, trees of these species produce large numbers of fruit that simply fall from their branches down to the forest floor, where the pulp is eaten by insects or eventually rots away, leaving behind dense clumps of intact seeds in exactly the same spot they landed. No vertebrate animal seems to bother with these fruits – not even large fruit bats that disperse seeds in an exozoochorous (gnaw on fruit, discard seed without swallowing) manner, or scatter-hoarding terrestrial rodents like agoutis and squirrels that bury seeds across the forest floor.

Calatola venezuelana, a classic "megafaunal" fruit that no current Amazonian animal seems to eat by Varun Swamy

Many eminent scientists have pondered this ecological mystery over the past decades, with perhaps the most succinct explanation provided in an article published in 1982 by Daniel Janzen and Paul Martin in the journal Science, titled: Neotropical Anachronisms - The Fruits the Gomphotheres Ate. As it turns out, unreasonably vicious spines and large fruits with undispersed seeds are the ecological vestiges of a group of very large animals – megafauna – that lived in the Amazon rainforest for millions of years until they abruptly went missing about 12-10,000 years ago. Their extinction coincides very closely with the original human colonization of the Americas, and evidence from fossil records indicates that their disappearance was primarily due to overhunting by the first human inhabitants of the Amazon basin.

Piles of Caryocar amigdaliforme seeds are common at Tambopata Research Center. The seeds bear a striking

resemble to a miniature cerebrum – hence the local name "cerebro de mono" or "monkey’s brain" (Photo: Daxs Coayla)

Now it all makes sense! For a young Astrocaryum palm to survive in a forest full of enormous animals weighing multiple tons, of course, it would invest in protecting itself with horrendously vicious spines, as a deterrent to a rampaging 20-foot tall, 4-ton giant ground sloth from trampling over it. And over 10,000 years ago, Calatola and Caryocar fruits were probably being gobbled whole by herds of elephant-like gomphotheres, carried away from fruiting trees and eventually dispersed in piles of "mega-feces".

In the present day, vicious spines and large, undispersed seeds are the "Ghosts of Megafauna Past" of the Amazon rainforest – adaptations of plants that co-evolved over evolutionary time with native megafauna but have not yet caught on to their absence in the past ~10,000 years.

So when you visit Tambopata and come across a pile of Caryocar seeds on the forest floor, or walk past an Astrocaryum trunk, take a moment to pay silent homage to the missing megafauna that once inhabited these forests, and be thankful for the contemporary large vertebrates – the spider monkeys, peccaries, and tapirs – that still do!